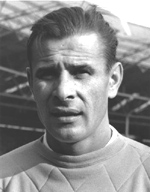

Gordon Banks

Considered by many to be the greatest goalkeeper of all time, Gordon Banks will forever be remembered for his save from Pele's header during the 1970 World Cup Finals. Yet those who saw Banks play knew he was capable of repeating such a feat on a cold December afternoon when all that was at stake was two points. He wasn't just great - he was consistently on top of his game and a Banks mistake was very rare indeed.

Considered by many to be the greatest goalkeeper of all time, Gordon Banks will forever be remembered for his save from Pele's header during the 1970 World Cup Finals. Yet those who saw Banks play knew he was capable of repeating such a feat on a cold December afternoon when all that was at stake was two points. He wasn't just great - he was consistently on top of his game and a Banks mistake was very rare indeed.

Yet but for a quirk of fate, he may neve have turned professional in the first place. Having been dropped by Sheffield Schoolboys, Banks had left full-time education in 1952 and had drifted out of the game. However, one afternoon he went along to watch local amateur side Millspaugh in action and was asked to play in goal after being spotted in the crowd because their regular keeper failed to turn up for the game. His performances for the club led to him being spotted and signed by Chesterfield, setting him on the path of World Cup glory.

First capped at the age of 25, he was the first England goalkeeper to play more than 33 times and the first to keep more than ten clean sheets. During his career he established a number of records at international level for England that remained until Peter Shilton came onto the scene.

But Shilton was unable to capture all of Banks's records. The goalkeeper still holds the England record of seven clean sheets in a row, which was finally ended by Eusebio's late penalty in the semi-finals of the 1966 World Cup, and played in 23 consecutive internationals without defeat between 1964-67. And of course, he is still the only English goalkeeper ever to win a World Cup Winners medal.

However, Gordon Banks's success on the international stage was not mirrored domestically. After winning the League Cup with Leicester City in 1964, he seemed destined to miss out on further Cup glory until finally winning the League Cup with Stoke City in 1972, having twice been a losing FA Cup and a League Cup Finalist with the Foxes during the 1960s.

He didn't have much luck with injury either. He missed a vital World Cup Quarter Final against West Germany in 1970 when he was struck down by a bad bottle of beer of all things the night before and his career was brought to an untimely end after he lost an eye in a road accident. He turned to coaching before temporarily resurrecting his career in the North American Soccer League.

A genuine legend of the game.

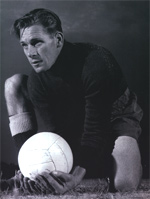

Lev Yashin

Famed for always wearing a distinctive all-black strip when playing (although initially, his kit was a very dark blue), Lev Yashin is one of the few keepers who could genuinely challenge Gordon Banks for the title of greatest goalkeeper of all-time.

Famed for always wearing a distinctive all-black strip when playing (although initially, his kit was a very dark blue), Lev Yashin is one of the few keepers who could genuinely challenge Gordon Banks for the title of greatest goalkeeper of all-time.

He made an unprecedented contribution to the game, going on to inspire future generations of goalkeepers, and challenged many of the traditional attitudes towards goalkeeping that were prevalent at the time. The big Russian was one of the first goalkeepers to command his entire penalty area and one of the first to do away with catching the ball; if punching or kicking was easier or more effective, he had no qualms in doing so.

A great athlete - he first found fame playing ice hockey and won the Soviet title in 1953! - Yashin displayed great courage between the sticks and possessed stunning reflexes and a flexibility that made him almost flawless. He was also credited with revolutionising the role of the goalkeeper, acting as an extra defender when required and by starting dangerous counter-attacks with his positioning and quick throws, rather than simply launching the ball down field.

First choice goalkeeper for the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1967, he won 78 caps in total and appeared in the final stages of three World Cups, attending a fourth in 1970 as one of the back-up keepers in Mexico. In 1956 he was a member of the Soviet team that won Olympic Gold in Melbourne and four years later he won the inaugural European Championship title with the USSR, picking up a runners-up medal four years later. Domestically, he only ever played for one club - Dynamo Moscow - where he won five league championships and three Cup titles, although legend has it that he conceded a soft goal scored straight from a clearance by his opposite number on his debut in a friendly in 1950.

In 1963 Lev Yahsin was voted European Footballer of the Year and remains the only goalkeeper to have ever won the honour. He was awarded the Order of Lenin in 1967 before retiring at the age of 41 in 1971 having kept an unprecedented 270 clean sheets (he is also rumoured to have saved over 150 penalties). He passed away in 1990.

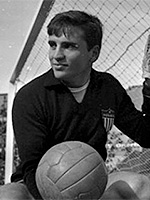

Peter Shilton

One of the great, driven players, Peter Shilton set out to become the best goalkeeper of all time. Legend has it that on being told he might not make the grade because he wasn't tall enough, Shilton went home and began a training regime that involved spending hours at a time hanging from the stairs in attempt to add inches to his frame. He wanted it that badly.

One of the great, driven players, Peter Shilton set out to become the best goalkeeper of all time. Legend has it that on being told he might not make the grade because he wasn't tall enough, Shilton went home and began a training regime that involved spending hours at a time hanging from the stairs in attempt to add inches to his frame. He wanted it that badly.

England's most capped player with 125 caps to his name, Shilton helped himself to a number of England goalkeeping records during his remarkable career - most matches, sixty-six clean sheets, captain fifteen times and second only in terms of age and length of career to Stanley Matthews. He's also England oldest ever captain, leading the team out at the age of 40 for the Third Place play-off vs. Italy in 1990. He played in the final stages of the World Cup 17 times - a British record - and kept 10 clean sheets, also a record. He went 499 - some say 500 - minutes without conceding a goal, overtaken only by Italy's Walter Zenga.

One of the few records he missed out on was Gordon Banks' record of seven consecutive matches without conceding a goal - but he came mightily close, twice reaching six games in a row.

Domestically, he won the League title with Nottingham Forest in 1978 and also enjoyed a couple of League Cup triumphs. He won two European Cups during his spell at the City Ground and was voted Man of the Match in the second of these when he single handedly kept Kevin Keegan's SV Hamburg at bay in 1980. He also made over 1000 league appearances, achieving his personal millennium milestone when he turned out for Third Division Leyton Orient in 1998. He played for nine clubs in total - Leicester City, Stoke City, Nottingham Forest, Southampton, Derby County, Plymouth Argyle, Wimbledon, Bolton Wanderers and Leyton Orient before finally hanging up his boots.

But for England managers Don Revie, who only picked him three times, and Ron Greenwood, who employed an oddball rotation when it came to selecting either him or his great rival Ray Clemence, who knows how many caps Shilton could have won. One of the true greats.

Bert Trautmann

Born in Bremen, Germany, Bert Trautmann overcame prejudice and open hostility - from both opposition supporters and his own - to become an unlikely folk hero in post-war Manchester. His route to Maine Road was even more unlikely.

Born in Bremen, Germany, Bert Trautmann overcame prejudice and open hostility - from both opposition supporters and his own - to become an unlikely folk hero in post-war Manchester. His route to Maine Road was even more unlikely.

His early life was spent growing up in a world of hyperinflation and the Hitler Youth. He was enlisted into the Wehrmacht at the outbreak of the Second World War and had an eventful campaign to say the least. Having initially been a paratrooper, he was court martialled after a practical joke behind the lines went wrong and ended up serving a three-month prison sentence. Eventually promoted to the rank of Feldwebel (sergeant), he fought on the Eastern Front, faced the Allies at Normandy and Arnhem, was buried under rubble in a cellar for three days and won five medals, including the Iron Cross (First Class). He was captured by the Russians and escaped, then captured by the Free French and escaped, also captured by the Americans and escaped before finally being captured by the British - who greeted him with the immortal line "Hello Fritz, fancy a cup of tea?"!

He eventually ended up at POW Camp 50 at Ashton-in-Makerfield where he saw out the last days of the war and enjoyed the odd football match. Originally a centre forward, he went in goal when injury prevented him from competing outfield. His natural talent was quickly recognised and he ended up at St. Helen's Town - where he his performances in the Lancashire Combination League first attracted the attentions of Manchester City.

Trautmann moved to City in 1949 but, unsurprisingly, the talented young keeper was not an instant crowd favourite. There was outrage from City fans and people throughout the country concerning the signing of a German player. There were threats of boycotts and letters of disapproval all arising from Trautmann's arrival at City. But he overcame these odds to become a legend at the Maine Road club and earn the respect of the football community.

He quickly established himself as one of the best goalkeepers in the country and would make 545 appearances in total for Man City. By 1952, his reputation was such that Schalke 04 sought to bring him back home to West Germany by offering City £1,000 for his services, but the club turned down the offer, believing Trautmann to be worth "twenty times more". He went to play in the 1955 FA Cup Final, becoming the first German to do so, but City lost 3-1 to Newcastle United. However, the following year Trautmann cemented his place in folklore when he broke his neck in a challenge with Birmingham City's Peter Murphy 15 minutes from time. He continued to play on, despite being in visible discomfort, and three days later it was discovered that he had dislocated five vertebrae, one of which was cracked in two. His efforts that season earned him the league's Player of the Year award, the first goalkeeper to win the award.

Trautmann was rewarded for his long and dedicated service to City with a testimonial, which saw a record 60,000 people attend and after his playing days were over he tried his hand at management with Stockport County before fulfilling a role as an overseas coach for the same German FA that had refused to pick him for their national side because he had the audacity to become a professional footballer (professionalism was still outlawed in Germany during the 1950s).

Sepp Maier

Born Josef-Dieter Maier, "Sepp" Maier began his footballing career at his local club, TSV Haar, but moved to Bayern Munich before he played he a senior game. He would stay in Munich for nineteen successful years, barely missing a game during this period, and between 1966 and 1977 he played almost 400 consecutive games.

Born Josef-Dieter Maier, "Sepp" Maier began his footballing career at his local club, TSV Haar, but moved to Bayern Munich before he played he a senior game. He would stay in Munich for nineteen successful years, barely missing a game during this period, and between 1966 and 1977 he played almost 400 consecutive games.

In 1966 he went to the World Cup finals in England as back-up to first choice Hans Tilkowski and despite failing to make an appearance as the Germans reached the final, he went on to establish himself as West Germany's first choice keeper four years later and played a major part as the Germans reached the semi-finals, only to lose to Italy in extra time.

Two years later he picked up his first international honour when West Germany won the European Championships and in 1974 he had his finest hour when West Germany hosted and won the World Cup, beating Holland in a tight final. He also enjoyed considerable success at club level during this period and was part of the Bayern Munich side that won three straight European Cups plus a World Club Cup and the UEFA Cup Winners Cup in 1968. Domestically, Maier won both the Bundesliga and DFB-Pokal four times but surprisingly failed to pick up another medal after 1976.

Nicknamed "Die Katze von Anzing (the cat from Anzing), Maier was a favourite with the Munich crowd and often played in distinctive long, black shorts. But his popularity stretched further afield and he won the German Player of the Year award three times to add to the Golden Glove he won after West Germany's victory in '74.

By the time the 1978 World Cup finals came around, Helmut Schön's side were no longer the force they once were and were eliminated in the second phase. This was to be Maier's last big tournament as a car accident in 1979 ended his career at the age of 35. Having won almost a century of caps for his country and 13 major trophies with Bayern Munich, he later joined the coaching staff both at Bayern and the German national team before retiring from the game.

Jack Kelsey

In an era when being a goalkeeper was a far more hazardous occupation than it is now, Kelsey stood out amongst the crowd. A former steelworker from Wales, the Wales international had the necessary physique and bravery to hold his own against the likes of Nat Lofthouse and other centre forwards who thought nothing of barging a goalkeeper into the back of the net.

In an era when being a goalkeeper was a far more hazardous occupation than it is now, Kelsey stood out amongst the crowd. A former steelworker from Wales, the Wales international had the necessary physique and bravery to hold his own against the likes of Nat Lofthouse and other centre forwards who thought nothing of barging a goalkeeper into the back of the net.

He joined Arsenal in the late Forties after being spotted playing for Winch Wen in his native Wales by former Gunner Les Morris and remained with the club for the rest of his career. He was famed for having a pair of hands "the size of dinner plates" and for rubbing chewing gum into his palms before each match to the help the ball stick - it must of helped because his handling was second to none. Although Kelsey was of a more rugged build than most, there was more to his game than brawn. His positional sense was ahead of its time and he commanded his area like no other. He was also prepared to venture beyond his penalty box to clear up any potential threat from the opposition - something that was unheard of at the time.

Unfortunately for Kelsey, he played at a time when Arsenal were rather a nondescript outfit and his only domestic honour was the League Championship in 1953. He excelled on the international stage, though, and won 41 caps for Wales - a British record for a goalkeeper at the time. He also played in the 1958 World Cup finals, where he helped his side reach the quarter-finals before going out to the eventual winners Brazil in a close fought contest. In addition to this, he represented Great Britain in an exhibition match against the rest of Europe in 1955 and was selected to play for London in the Inter Cities Fairs Cup - the forerunner of the UEFA Cup - a year later.

His career was cut short however by a back injury sustained in an international against Brazil in 1962. Despite a couple of attempts at a comeback, he was forced to hang up his gloves but he remained at Highbury, were he continued to work for Arsenal Football Club behind the scenes as their commercial manager in later years. He died in 1992.

Neville Southall

Legend has it, that when Neville Southall started out with Bury, he was banned from training with the rest of the squad because they were getting a bit despondent that he was ruining their shooting practice by saving everything thrown at him. But that was Neville Southall all over - even in training he never gave less than 100%.

Legend has it, that when Neville Southall started out with Bury, he was banned from training with the rest of the squad because they were getting a bit despondent that he was ruining their shooting practice by saving everything thrown at him. But that was Neville Southall all over - even in training he never gave less than 100%.

A former hod-carrier and dustman in Llandudno, Southall began life as a centre half. He was good enough to have trials with Crewe Alexandra and Bolton Wanderers but never made the grade. Instead, he went between the posts for Llandudno Swifts and quickly moved up the football ladder. After brief spells with Conway United and Bangor City, he joined non-league Winsford where he was spotted by Bury, who paid £6000 for his services.

After just 39 games for the Shakers, Southall was snapped up by Everton, completing an amazing transformation - in just less than two years, he had gone from working on a building site to playing First Division football. For the next sixteen years he would remain the Toffees' first-choice keeper, experiencing all their highs and lows.

The honours came thick and fast during those early days. Everton were experiencing something of a revival under Howard Kendall and within the space of three won the League, FA Cup and the Cup Winners' Cup. Indeed, Southall was voted Player of the Year in 1985 when the Blues won the championship but the Heysel disaster cut short Everton's dominance as the team broke up. And while others went on to enjoy big money moves to the continent, Southall stayed behind, clocking up the appearances.

Although successful on the domestic front, the big Welshman enjoyed little success on the international scene and although he was an established World Class player, he never played in a major tournament. The closest he got was in 1993, when Wales narrowly missed out on World Cup qualification. Nevertheless, he racked up 91 caps - a national record.

Southall played over 700 times for Everton - a club record - and was the first player to make 200 appearances in the Premiership. As he matured with age, many expected him to retire gracefully, but Big Nev confounded the critics and just kept on going, adding a second FA Cup winners medal to his collection in 1995. But time soon caught up with Southall. After loan spells with Southend United and Stoke City, plus a spell with Torquay United, he finally retired before making a comeback for Bradford City at the ripe old age of 42 in the Premiership!

Leigh Richmond Roose

Leigh Richmond Roose didn't have to be a goalkeeper. The boy from North Wales was a qualified doctor of bacteriology and was rich enough to once hire his own train to get him to an away game on time. But by the time he died - killed during the First World at the Somme - he created a football legend that survives to this day (examples of which can be found across this site).

Leigh Richmond Roose didn't have to be a goalkeeper. The boy from North Wales was a qualified doctor of bacteriology and was rich enough to once hire his own train to get him to an away game on time. But by the time he died - killed during the First World at the Somme - he created a football legend that survives to this day (examples of which can be found across this site).

During a game he could usually be found leaning casually against the goalpost without a care in the world, as if he was waiting for a bus. Rumour has it that he would occasionally fall asleep if left alone too long. When teammates complained, he tried to stave off sleep by talking to the crowd. He also had a wicked sense of humour and was not adversed to playing the odd practical joke on his colleagues. He once turned up for a game with his hands covered in bandages and insisted he was fit enough to play. Sure enough, once the bandages were off, he gave an assured display between the sticks, proving that there was nothing wrong with his hands in the first place. But it was his handling skills that led to the FA changing the rules of the game. Until Roose came along, goalies had been allowed to handle the ball outside the eighteen-yard box. The Welsh custodian interpreted these rules somewhat differently to other goalkeepers and would regularly carry the ball to the other end of the field.

Roose's jersey was also a subject of mythology. He swore that he could only keep goal in one particular top made by one particular person in one particular way. Having kept goal for seventeen years for a number of clubs, including Aston Villa and Celtic, and played twenty-four times for Wales, his shirt must have been either very worn or incredibly smelly by the end of his career, especially as he insisted on wearing the same undershirt that was never washed it case brought him bad luck.

When he wasn't leaning against the goalposts or testing the sanity of his club colleagues, Roose could be a pretty athletic keeper. Contemporary records show that his 'daring gymnastics in goal' made him 'a hero to every boy in the land'. He was one of the first goalkeeping greats to emerge from the game and his record speaks for itself. He also had an unusual sporting approach to the game. On his debut for Celtic in 1910, he ran up the pitch to shake hands with the scorer of the opposition's third goal. History doesn't record what his team-mates thought of this gentlemanly gesture.

In many ways he was the spiritual ancestor of Bruce Grobbelaar, brilliant but erratic, with the capacity to make you wonder if was actually watching the game. And like that other famously flamboyant Welsh goalie, Neville Southall, he was proof that you didn't have to be miserable to be a keeper! But his most impressive contribution to the evolution of the game was to be one of the few players who've actually managed to get the laws of the game changed.

Pat Jennings

If ever there was a goalkeeper that could be described as atypical of the breed, it was Pat Jennings. Unorthodox, unflappable, respectable and polite, Jennings commanded his penalty box with an air of nonchalance and calmness that would shame Peter Schmeichel into retirement. Yet despite never receiving any formal kind of coaching - or even because of it - he become one of the greatest goalkeepers the game has ever seen.

If ever there was a goalkeeper that could be described as atypical of the breed, it was Pat Jennings. Unorthodox, unflappable, respectable and polite, Jennings commanded his penalty box with an air of nonchalance and calmness that would shame Peter Schmeichel into retirement. Yet despite never receiving any formal kind of coaching - or even because of it - he become one of the greatest goalkeepers the game has ever seen.

Born in Newry, Northern Ireland, Jennings grew up playing Gaelic Football before signing for his local side as a teenager. He first caught the eye playing in a Youth Tournament at Wembley at the age of 17 and was signed by Watford shortly afterwards. His subsequent performances for the Hornets earned him International recognition and a transfer to Tottenham Hotspur in 1964.

There he arguably enjoyed the most successful spell of his career, winning the FA Cup, two League Cups and the UEFA Cup in quick succession. However, believing he was past his best, Spurs foolishly sold him to local rivals Arsenal for £40,000 in 1977, where he enjoyed further success and played on for another eight seasons. He appeared in three more FA Cup Finals and a Cup Winners Cup Final before capping his career with an appearance at the World Cup Finals, where he played in the Northern Ireland side that unexpectedly beat host nation Spain to progress to the Quarter Finals.

Such was his stance in the game that he came out of retirement to play in the 1986 finals in Mexico, winning his record 119th cap on his 41st birthday against Brazil.

One of the reasons he was so successful was down to the size of his hands - which were as big as a pair of satellite dishes (or thereabouts). His 'Lurgan shovels', as manager Billy Bingham liked to call them, helped him pull off spectacular one-handed saves which didn't see possible and he had the habit of breaking the hearts of many a centre forward by clawing the ball out of the air single-handedly and holding onto it.

But it wasn't just about his hands - it was his whole approach to the game. A late starter, his lack of formal training meant he avoided the bad habits and strict codes of conducts of his predecessors, and he broke the mould by willingly using other parts of his body to keep the ball out of the net. He was the first to use his feet to good effect and underlined the strength of his kicking by scoring from a goal kick during the 1967 Charity Shield match against Manchester United.

Ray Clemence

History has been kind to Ray Clemence. Some would say too kind but in 2001, a poll conducted by Total Football placed the former Liverpool and England shot-stopper on top spot, beating the likes of Pat Jennings, Gordon Banks and Peter Shilton. Okay, there's no doubting the guy was a great talent, but he wasn't that good!

History has been kind to Ray Clemence. Some would say too kind but in 2001, a poll conducted by Total Football placed the former Liverpool and England shot-stopper on top spot, beating the likes of Pat Jennings, Gordon Banks and Peter Shilton. Okay, there's no doubting the guy was a great talent, but he wasn't that good!

That doesn't mean Clemence wasn't a quality goalkeeper. Far from it - his natural athleticism and agility combined with his shot-stopping prowess made him one of the best of his generation and when he was at the top of his game, there truly was no one better, such as when he made save after save to earn England a goalless draw in Rio in 1977.

Born in Skegness, Big Clem started out at his home club where he made up the short-fall in his earnings by working as a deck chair attendant in the summer. After a trial with Notts County, he joined Scunthorpe United where he was spotted by Bill Shankly. Shankly knew a bargain when he saw one and paid £18,000 to take him to Liverpool. After a couple of years in the reserves, he displaced Tommy Lawrence as first choice keeper in 1970 and went on to play 665 first team games for the Reds, keeping an incredible 335 clean sheets along the way.

At club level, he won everything there was to win including three European Cups, five League Championships, two UEFA Cups and two FA Cups and he ended up with a haul of 13 domestic medals, becoming one of the country's most decorated players in the process. His international career, however, was less auspicious.

While Clemence was winning everything with Liverpool in Europe, England were having a woeful time of it on the international stage. They failed to qualify for the 1974 World Cup Finals in dramatic fashion then didn't even get a chance to turn up at the 1978 Finals after an horrendous start to their qualifying campaign.

However, despite having to compete with the likes of Peter Shilton and Joe Corrigan, Clemence won 61 England caps in total and was the first goalkeeper to captain his country since Frank Swift. Yet he never really achieved much beyond that. Although he went to Spain for the World Cup in 1982, he was no longer first choice and watched the action from the bench. He had better luck in the 1980 European Championships but England once again failed to rise to the occasion and went out in the opening group stages.

Clemence may finally be remembered as the man who deprived Peter Shilton of another few dozen caps, which is unfair but perhaps not completely so. He could have gone to Mexico in 1986, but prematurely decided to retire from the England scene when Bobby Robson took over - a decision that seems even more hasty now in light of Shilton's subsequent achievements and the fact he played in the FA Cup Final a year later with Tottenham Hotspur. But Clem was never ready to be second best, a trait he shared with his rival for all those years and one to be respected.

Joe Corrigan

People often forget just how good Joe Corrigan was in goal. Sure, they remember the name, they may have even seen him play once or twice but he always be remembered as England's third choice goalkeeper. And for that, you have to blame a certain Ray Clemence and Peter Shilton.

People often forget just how good Joe Corrigan was in goal. Sure, they remember the name, they may have even seen him play once or twice but he always be remembered as England's third choice goalkeeper. And for that, you have to blame a certain Ray Clemence and Peter Shilton.

With two such outstanding goalkeepers competing for the one jersey it was always going to be hard to get a look-in on the international scene. Had he been born elsewhere, he would probably have been an automatic first choice but Joe was as English as they come, and to be honest, he fared better than most other keepers unfortunate enough to playing around that time. He may have only won nine caps but it was a lot more than the likes of Phil Parkes, Jim Montgomery and Bryan King ever won, despite their obvious talents.

He began his career with Manchester City in 1968 yet struggled to establish himself as the club's first choice keeper and was even loaned out to Shrewsbury Town at one point. But he overcame this confidence crisis to blossom into a keeper to rank alongside those other City legends, Frank Swift and Bert Trautmann, and was part of the squad that won the League Championship, UEFA Cup and League Cup.

A giant of a man, he never looked much of an athlete but his 6ft 4ins, 15 stone frame belied a remarkable agility and amazingly quick reflexes. He could dominate games and turn matches, and despite being on the losing side, he was named Man of the Match in the 1981 FA Cup Final replay. He never let his country down neither - big Joe was only ever on the losing side once - and it could be argued that in Corrigan, Shilton and Clemence, England boasted the best trio of goalkeepers ever to appear in a World Cup squad when they lined up for the 1982 finals.

Having played 592 games in 16 seasons, his career at Maine Road came to an untimely and rather messy end when he was sold to the American side Seattle Sounders for a paltry £30,000. Manchester City were going through one of their legendary bouts of madness at the time and manager John Benson, who would be shown the door himself shortly after, decided Corrigan was surplus to retirements. He eventually returned to England and Brighton & Hove Albion before retiring to the more serene life of a goalkeeping coach with Liverpool. City, meanwhile, were to spend much of the 1980s yoyo-ing between the First and Second Division as they struggled to find a replacement for the keeper they had written off only seasons before.

Ted Ditchburn

In an era when the England team was selected by an anonymous panel, Ted Ditchburn won a paltry six caps in an international career that spanned eight years. He should have won more. A lot more.

In an era when the England team was selected by an anonymous panel, Ted Ditchburn won a paltry six caps in an international career that spanned eight years. He should have won more. A lot more.

Remarkably, he was capped before and after contemporaries Bert Williams and Gil Merrick, both of whom were selected over twenty times each. Yet despite their shortcomings - Merrick conceded an amazing thirty goals in his last ten games while Williams played in an England side that lost far too many games - Ditchburn often found himself in the international wilderness. The probable reason being that he was far too unorthodox for the selectors liking.

Ted was the goalkeeper's goalkeeper. He stood out amongst the crowd during the 1950s thanks to his physique and fitness, which were the result of serving in the army as a PT instructor. But it wasn't just for his saves that he was so celebrated - Ditchburn was a tactical innovator. In a time when keepers would punt the ball down field as far as possible whenever they go the ball, big Ted opted to roll it out to one of his full-backs, inventing the patient build up in the process.

It doesn't sound particularly revolutionary now, but Ditchburn's plays laid the foundations for manager Arthur Rowe's famous 'push and run' strategy, which moved the emphasis away from route one and towards short, controlled passes. Ditchburn was naturally modest about the whole affair, blaming his "awful kicking" as the real reason behind the switch, but the move paid dividends as Spurs won the Second and First Division titles back-to-back in 1949/50 and 1950/51.

He originally made his debut for Tottenham in 1940 during a wartime league match but had to wait six years for his "official" debut. Despite having lost a large chunk of his career to the War, Ditchburn went on play over 400 games for the White Hart Lane side before retiring after breaking his finger in a game against Chelsea in 1958.

Peter Schmeichel

In today's hyped-up football world, the words 'great' and 'legend' are often overused to describe one-footed journeymen who may have popped up to score a vital goal for their club before being transferred to another for more millions than anyone cares to mention. But when it comes to Peter Schmeichel, such tributes are richly deserved for a goalkeeper of truly awesome talent.

In today's hyped-up football world, the words 'great' and 'legend' are often overused to describe one-footed journeymen who may have popped up to score a vital goal for their club before being transferred to another for more millions than anyone cares to mention. But when it comes to Peter Schmeichel, such tributes are richly deserved for a goalkeeper of truly awesome talent.

Schmeichel may arguably be the greatest goalkeeper the game has ever seen. He certainly was the nosiest. A giant of a man, he appeared to fill the goal when at full stretch and his gigantic frame and enormous physical presence belied a subtle agility which enabled him to produce some remarkable saves, not least against Rapid Vienna in 1996 when he somehow clawed Rene Wagner's header away from the goal-line during a Champions League tie.

What made Schmeichel unique was his style of goalkeeping. His unorthodox approach was a distance cousin of the style of goalkeeping that made Pat Jennings famous and in many ways re-wrote the textbook. He'd used every part of his anatomy to keep the ball out of his net and his quick vision and expert distribution could quickly turn a defensive position into an attack. What's more, he stamped his authority and commanded his area like no goalkeeper before or since and would often give his defence merry hell if the opposition got so much as a weak header on target.

But this approach did wonders for Sir Alex Ferguson's Manchester United and while people were quick to applaud the talents and influence of Eric Cantona, Schmeichel's influence on turning United's fortunes around cannot be underestimated.

If that wasn't enough, there was also an attacking side to his game that racked up an impressive thirteen career goals - including one at international level - and his forays into the opposition's penalty area could lead to all sorts of confusion and indirectly led to Teddy Sheringham's late equaliser against Bayern Munich in the 1999 European Cup Final.

That European title was probably the pinnacle of the Great Dane's career and capped an impressive career with the Old Trafford side that saw him walk away with five Premier League titles, three FA Cup and one Champions League winners' medals to add to the European Championship medal he won with Denmark in 1992.

A true great, the likes of which we may never see again.

Peter Bonetti

Despite making over 700 appearances for Chelsea and picking up seven England caps, Peter Bonetti will always be harshly remembered for one bad game.

Despite making over 700 appearances for Chelsea and picking up seven England caps, Peter Bonetti will always be harshly remembered for one bad game.

Having not played a match for two months, Bonetti was called on to deputise for Gordon Banks, who had been taken ill after drinking a dodgy bottle of beer, in the World Cup Quarter-Final against West Germany and put in a strangely uncertain display which saw the Germans come from 2-0 down to win 3-2. Bonetti was never picked for England again and his reputation has suffered thanks to that performance. But that one game belies the fact that Peter Bonetti was a high-class keeper who would have won more caps but for Banks.

Bonetti was always going to be something special. A stylish keeper, who was easily the most spectacular goalie of his day, he made his debut for Chelsea at the age of 18 after his mother wrote to then manager Ted Drake, requesting that he give her son a trial. He kept a clean sheet and went on to star in the Blues' impressive cup runs in the late 60s, winning the FA Cup, League Cup and Cup Winners' Cup, turning in a brilliant display in the replay win over Real Madrid. Nicknamed The Cat, he played for Chelsea 729 times between 1959 and 1979 - a record at the time - and once managed to keep 21 clean sheets in a single season.

Many compared his style of keeping to the continental goalies of day and he certainly had an element of flamboyance in his game. He was good in the air and had a certain agility which allowed him to change direction in mid-flight.

His international stats also make impressive reading too. Prior to the game against West Germany in Leon, Bonetti had six wins out of six to his name, keeping five clean sheets and conceding just one goal, and produced a match-winning display against Portugal at Wembley. Such was his reputation that Pele once went on record as saying "The three greatest goalkeepers I have ever seen are Gordon Banks, Lev Yashin and Peter Bonetti."

And who are we to argue with that?

David Seaman

When people look back on David Seaman's career in ten years time, they won't automatically remember the good times - the Championships, FA Cups and European success with Arsenal or the near misses with England. Instead they'll recall the two occasions that he was beaten from long range and the stupid ponytail that he decided to grow before Euro 2000. But that, as they say, is football.

When people look back on David Seaman's career in ten years time, they won't automatically remember the good times - the Championships, FA Cups and European success with Arsenal or the near misses with England. Instead they'll recall the two occasions that he was beaten from long range and the stupid ponytail that he decided to grow before Euro 2000. But that, as they say, is football.

At his peak, David Seaman was one of the best goalkeepers in the history of the English game, mentioned in the same breath as Peter Shilton and Gordon Banks. During Euro 96, he was in the form of his life as England narrowly missed out on another triumph on home soil and he achieved national hero status when he saved Gary McAllister's penalty against Scotland.

Seaman's rise to the top was progressive rather than overnight. He began his career at Leeds United but was considered surplus to requirements and had spells with Peterborough United and Birmingham City before transferring to Queen's Park Rangers. It was while he was at Loftus Road that he began to attract attention and in 1988 he made his England debut against Saudi Arabia. Injury kept him out of the World Cup in 1990 but in the summer of the same year he was snapped up by George Graham and began a love affair with Arsenal that was last thirteen years.

Seaman's commanding presence and organisational skills were vital to The Gunners' back-line and he became part of the back-bone of the side that went on to lift the League Championship, FA and League Cups before going on to enjoy European success in the Cup Winners' Cup. He would eventually play over 500 games for the North London club, adding a number of winners medals to his collection along the way, before eventually joining Manchester City on a free transfer.

Having seen off the challenges of Alex Manninger and Richard Wright at Arsenal, Seaman went on to make the England jersey his own as well. He was his country's first-choice goalkeeper for nearly eight years and played in four successive major tournaments. He made over 60 caps for his country and was still considered the country's best keeper at the ripe old age of 40. Eventually he was displaced, but more through injury than loss of form.

In the end, his career was neatly book-ended by the aforementioned long-range efforts from Nayim in the 1995 Cup Winners' Cup Final and Ronaldinho in the 2002 World Cup Finals. Nayim's effort seemed to give him the strength and resolve to reach the very peak of the game and in 1996, there were few goalkeepers better than Seaman on the world stage. However, despite his performances against Sweden, Argentina and Demark, people will always remember Ronaldinho's free-kick for Brazil and the finger of blame was - unfairly - pointed at the goalkeeper as England limped out of a World Cup they could've won.

A shoulder injury eventually ended his career in 2003, but by then David Seaman had earned his corn and done enough to be considered a true great, despite that silly ponytail...

Ronnie Simpson

Goalkeepers are odd creatures - some of them start off with a bang, others seem to go out with a bang. Ronnie Simpson, on the other hand, decided to do both, in a career that lasted nearly 25 years.

Goalkeepers are odd creatures - some of them start off with a bang, others seem to go out with a bang. Ronnie Simpson, on the other hand, decided to do both, in a career that lasted nearly 25 years.

Son of the former Rangers centre-half Jimmy, Ronnie made his first class debut at the age of 14 when he turned out for Queen's Park in the summer of 1945 and stayed with the Glasgow side until the summer of 1950 when he signed professional forms with Third Lanark. By the time he reached twenty, he had played over 100 times for The Spiders and represented both Scotland and Great Britain at amateur level, making an appearance in the Olympic games along the way.

His performances with Third Lanark earned him a £8,750 (big money back then!) move to Newcastle United in February, 1951, and it was at St. James' Park that Simpson became a star. Having dislodged veteran Jack Fairbrother from the starting line-up, he took his place alongside the likes of Jackie Milburn and Joe Harvey and was part of the Newcastle side that won the FA Cup in 1952 and 1955, becoming the first goalkeeper to win two FA Cup winners medals since Dick Pym in the 1920s. And he was still only 24.

Despite enjoying success with Newcastle, Simpson failed to impress Scotland's international selectors and the only recognition he received during this period was in the form of two "B" caps against England, four years apart.

After ten years and nearly 300 first-team appearances, Simpson moved back north of the border, joining Hibs shortly before his 30th birthday. The likeable goalkeeper had fallen out of favour at St. James' Park and had been languishing in the reserves. His career seemed to be coming to a close, but he found a new lease of life at Easter Road and played a key role in Hibernian's march to the semi-finals of the 1961 Fairs (UEFA) Cup competition while Newcastle were relegated.

In 1964, Simpson's career took another turn. Hibs manager Jock Stein decided that the goalkeeper was surplus to requirements and just when it seemed like it was time to hang up his gloves, Celtic came in with an offer of £4,000. He joined the Parkhead side as cover for John Fallon and many saw the move as one final pay-day.

Simpson managed a couple of appearances for The Hoops before Stein became manager. Things didn't look too bright for the goalkeeper but when the Stein's hand was forced, Simpson got his chance and neither ever looked back. He went on to play a total of 188 times for the club and managed to keep 91 clean sheets, collecting four championship medals, one Cup and three League Cup medals along the way. But his greatest prize came in 1967, when he was part of the historic Lisbon Lions side that won the European Cup against Inter Milan.

Simpson also finally got the international recognition he deserved and finally made his debut against England at the tender age of 36 as Scotland beat the reigning World Champions 3-2 at Wembley. He went on to win five caps in total and was named Player of the Year by the Scottish Football Writers Association in 1967 before retiring in 1970.

Harald Schumacher

Despite playing in two World Cup Finals and winning the European Championships with West Germany - not mention a very successful club career, Harald Schumacher will always be remembered for one thing: his "tackle" on Frenchman Patrick Battiston.

Despite playing in two World Cup Finals and winning the European Championships with West Germany - not mention a very successful club career, Harald Schumacher will always be remembered for one thing: his "tackle" on Frenchman Patrick Battiston.

Schumacher's assault - hip first - left Battison unconscious on the floor, minus a few teeth, and out of the game while the German goalkeeper escaped without so much as a booking before playing a major role in the subsequent penalty shoot-out that decided the game. A French national newspaper conducted a poll shortly afterwards to find the most hated man in France, and Schumacher managed to beat even Adolf Hitler (who finished second) into first place.

However, despite that tackle and underneath the porn star appearance, Schumacher was one of the best goalkeepers of his generation. The last line of defence of one of the strongest international teams ever to grace the field of play, he was twice voted German Footballer of the year and only Hans-Peter Briegel denied him an unprecedented hattrick of wins in the mid-1980s.

Schumacher spent almost his entire career with one club - 1.FC Koln - and played a record 422 times for the Bundesliga club between 1972-1987. He also had brief spells with Schalke, Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund but he will always be associated with "Der FC" in his native Germany, where he won the League title, Cup and UEFA Cup.

A strong-willed, athletic goalkeeper - if a bit eccentric, the former German number one played 76 times for his country, making his debut in 1979 against Iceland as a substitute for Sepp Maier, but his style and approach to the game - he often went through yoga routines before big games - were not popular with everyone. He had to fight off several challenges for the goalkeeper spot during his international career, including SV Hamburg's Uli Stein, who was eventually sent home from the 1986 World Cup Finals in frustration having been unable to dislodge Schumacher, who went on to finish second behind Diego Maradona in FIFA's Golden Ball vote to find the Player of the Tournament.

Schumacher went into management after hanging up his gloves and is still active in the German game today. However, over twenty years later, the clip of him charging into Battiston (who, incidentally, held no grudges and invited the goalkeeper to his wedding!) is still being aired on football shows up-and-down the country. A much underrated keeper, who, unfortunately, will never command the respect - especially in the UK - that his talents deserve.

Ubaldo Fillol

Arguably Argentina's greatest ever goalkeeper, Ubaldo Fillol didn't really look like a footballer. Indeed, his long, shaggy hair and penchant for baggy shorts would not have looked out of place on a Californian surfing beach. But in a 21-year-career, that included spells in Spain and Brazil as well as that World Cup win with Argentina in 1978, the charismatic keeper established himself as one of the best of the modern game.

Arguably Argentina's greatest ever goalkeeper, Ubaldo Fillol didn't really look like a footballer. Indeed, his long, shaggy hair and penchant for baggy shorts would not have looked out of place on a Californian surfing beach. But in a 21-year-career, that included spells in Spain and Brazil as well as that World Cup win with Argentina in 1978, the charismatic keeper established himself as one of the best of the modern game.

Born in San Miguel del Monte in 1950, "El Pato" (The Duck) made his professional debut in 1969 with Quilmes and although he had to wait another two season before finally establishing himself as their Number One, his early performances caught the eye of Racing Club, who signed him in 1972. In his first season with his new club, Fillol saved six penalties - an Argentinean record at the time - and quickly enhanced his reputation with a string of superlative performances between the posts. River Plate were certainly convinced and signed the goalkeeper at the start of the 1973 season.

Fillol went on to enjoy 11 successful years with the Argentinean giants as they dominated the national league but his greatest triumph came in 1978.

Four years early, during the 1974 tournament in West Germany, Fillol had been part of Argentina's squad as a reserve keeper, but after a disappointing second phase - which saw them lose to Brazil and Holland - he replaced first choice Daniel Carnevali in their final game against East Germany to make his World Cup tournament debut. Many expected Fillol to succeed Carnevali, but in the lead up to the 1978 Finals, manager César Menotti had favoured Hugo Gatti. However, Gatti was axed after a string of unconvincing performances by the host nation and Menotti decided to go with Fillol.

Fillol repaid his manager's faith with a string of excellent performances throughout the tournament as Argentina controversially marched to the final. In the second round he kept three clean sheets and saved a penalty by Poland's Kazi Deya which later proved decisive. In the final, Fillol frustrated the Dutch as he turned in his most impressive performance as the host nation won the trophy in extra time and was later voted Goalkeeper of the Tournament by the world's press.

He eventually retired from the National Team after more than a decade of service in 1985 - having competed in the 1982 Finals in Spain - with a record 58 caps to his name. He enjoyed a further successful five years with the likes of Flamengo, Athletico Madrid and Racing Club before moving into management.

Gyula Grosics

Dressed in black from head-to-toe, Gyula Grosics was the unmistakable last line of defence of the "Mighty Magyars" - the legendary Hungarian team of the early fifties who seemed destined to sweep all before them until they met West Germany in the 1954 World Cup Final. Until that game, Hungary had gone almost four years and played 33 games without tasting defeat.

Dressed in black from head-to-toe, Gyula Grosics was the unmistakable last line of defence of the "Mighty Magyars" - the legendary Hungarian team of the early fifties who seemed destined to sweep all before them until they met West Germany in the 1954 World Cup Final. Until that game, Hungary had gone almost four years and played 33 games without tasting defeat.

Born in 1926, Grosics grew up in the Tatabanya district of Hungary and by the time he was thirteen, he was well on his way to becoming a professional goalkeeper. The Second World War interrupted his progress but he eventually ended up at Honved and made his international debut in 1947 at the age of twenty-one. He would go on to enjoy a fifteen-year international career that would include participation in three World Cups and an Olympic Gold Medal at the 1952 Games in Helsinki.

A tall, athletic, imposing figure, Grosics was one of the Magyars' genuine World-class players. He may have been overshadowed by the likes of Puskas, Hidegkuti and Kocsis, but his contribution to that run of 33 games cannot be underestimated. Aside from the saves that made his reputation, Grosics was also one of the first goalkeepers to ever leave his box as the Hungarians set about revolutionising the game.

The Golden Team typically attacked as a unit, employing a "W-W" 4-2-4 formation with the backline moving into the opposing half. However, this adventurous style of play was open to counterattacks, often via a long-ball over the top, but coach Gustav Sebes recognised this threat and utilised Groscis natural athleticism by getting him to act a sweeper, often sprinting off his line to clear loose balls.

This unorthodox of attack system often confused the opposition and the team reached their zenith in 1953 when they went to Wembley and beat England 6-3 without breaking sweat. The result had major shockwaves through British football. Yet despite all evidence to the contrary - the deep-lying centre forward, the on-rushing goalkeeper and the interchanging of positions - it was years before the lessons from that game were finally learnt.

But despite losing only once in 50 games, The Golden Team's star soon began to fade. Following that infamous defeat to West Germany, the side returned to home to Hungary - where victory had been so certain - to vilification and retribution. Grosics himself was arrested later that year on charges of treason, placed under house arrest and barred from playing for 13 months.

He was eventually released and transferred to his home side Tatabanya, but despite his modest surroundings, he was still selected for the National side. However, by the time the uprising of 1956 had ended, Grosics was back with Honved, who just happened to be on tour at the time. Despite calls from the Communist regime, the team refused to return home and Grosics was offered a contract with Flamenco of Brazil. But, while the likes of Puskas and Kocsis went on to play Spain, the keeper - patriotic to the last - eventually returned home to Hungary with his family and resumed his playing career.

Jean-Marie Pfaff

Goalkeepers are an odd bunch but even the most eccentric of this exclusive club considered Jean-Marie Pfaff a bit loopy. A renowned practical joker, his pranks were often the bane of his teammates, but such was his talent that they often overlooked his mischievous streak in return for a clean sheet in the next game. Pfaff usually obliged.

Goalkeepers are an odd bunch but even the most eccentric of this exclusive club considered Jean-Marie Pfaff a bit loopy. A renowned practical joker, his pranks were often the bane of his teammates, but such was his talent that they often overlooked his mischievous streak in return for a clean sheet in the next game. Pfaff usually obliged.

A keeper of undeniable talent, he started his professional career earlier than most, signing his first contract with SK Beveren at the age of six. Beveren's faith in the prodigious goalkeeper was duly repaid twenty years later when a Pfaff inspired side won the Belgian Championship in 1979. But by then, most of Belgium knew just what a special talent he was. At the age of 23, he made his debut for the national side against Holland, and although the Red Devils lost the game, Pfaff announced his arrival on the international stage by saving a penalty. And in 1978 he won the "Soulier d'Or" (The Golden Boot) after leading the Waasland club to victory in the Belgian Cup.

But his pranks were not always to everyone's taste and he almost missed one of Belgium's greatest triumphs on the international stage when he was dropped from the national side just before the 1980 European Championships. He was eventually recalled and, despite being considered pre-tournament outsiders by the bookies, played his part in the Red Devils' march to the final. Belgium lost in the last minute to West Germany, but it was the start of a golden era for Belgian football, as they qualified for the next three major tournaments.

Following his performances in the 1982 World Cup finals in Spain, Pfaff began to attract the attention of some of Europe's big clubs but many were put off by his outlandish behaviour and extravagant goalkeeping style. Bayern Munich eventually decided to take a chance on him, and like Beveren before them, they were not to be disappointed. The German club won three Bundesliga Championships in succession (1985-87) plus two German Cups in 1984 and 1986 with the Belgian in goal.

The mid-Eighties were incredibly successful for Pfaff both domestically and at international level. In 1984 Belgium once again qualified for the European Championship and in 1986 they enjoyed a run to the semi-finals of the 1986 World Cup in Mexico that included an epic penalty shoot-out against Spain which once again elevated the goalkeeper to hero status in his homeland. But not even Pfaff could prevent a Maradonna-inspired Argentina from winning the competition.

After such a triumphant period, it came as little surprise when Pfaff beat off competition from the likes of Neville Southall and Peter Shilton to become the first keeper to be voted World's Best Goalkeeper by the International Federation of Football History & Statistics in 1987.

Pfaff continued to play for Belgium - eventually amassing 64 caps - and later played for Trabzon Sport and SK Lierse. But after retiring from the game, the joker inside the goalkeeper came to the fore and Pfaff became a TV Presenter, later fronting his own reality TV show - The Pfaffs - just to add weight to the theory that all goalkeepers are nuts.

Jürgen Croy

Jürgen Croy is something of an unsung hero in the world of goalkeepers. Chances are that you've probably never heard of him, but had he born on the other side of the Wall he could have very well been playing in the 1974 World Cup Final instead of Sepp Maier - he was that good.

Jürgen Croy is something of an unsung hero in the world of goalkeepers. Chances are that you've probably never heard of him, but had he born on the other side of the Wall he could have very well been playing in the 1974 World Cup Final instead of Sepp Maier - he was that good.

Born in the city of Zwickau, Croy spent his entire career with his hometown club, BSG Sachsenring Zwickau (now known as FSV Zwickau), playing nearly 400 top flight matches. He earned his first international cap at the tender age of twenty and kept a clean sheet as East Germany beat Sweden 1-0 and would go on to play 94 times for his country in an international career spanning fourteen years, keeping another clean sheet in his last appearance at the age of 34 against Cuba. But it was during the 1974 World Cup Finals that Croy came to the attention of the football world.

Drawn in the same group as their neighbours, the East Germans - with their outdated blue shirts with GDR emblazoned on the front - upset the form book by beating their counterparts from the West 1-0 in the final game to top the group. And although they were eventually undone by Brazil and Holland in the next round, they went home with their heads held high. None more so than Croy, who, with his excellent saves and reflex reactions, had captured the admiring glances of many.

It was during this period that Croy was at his best and experienced the most success. The 1974 team had built upon the foundations laid by the Olympic squad of 1972, who had walked away with the Bronze medal in Munich, and in 1976 they went all the way and won Gold at Montreal. On the domestic front, Croy won his second East German Cup Final with BSG in 1975, enjoying a run to the Semi-Final of the Cup Winners' Cup the following season. And it was during this period that the outstanding shot stopper was elected East German Football of the Year three times, in 1972, '76 and '78, not to mention being awarded the title of Honorary Citizen of the city of Zwickau in 1976.

Despite winning the East German Cup in 1967 and 1975, the dominance of teams like Dynamo Dresden and FC Carl Zeiss Jena restricted Croy's opportunities to shine in European competitions, which partly goes someway to explaining his partial anonymity in the West. However, his ability to stay at the top of his game earned him rave reviews in both the East and West German media and he deservedly made the Top Fifty of the International Federation of Football History and Statistics' Goalkeepers of the Century.

Ricardo Zamora

Ricardo Zamora Martinez was, is and probably forever will be one of the biggest names in Spanish football. But his reputation extends beyond the Iberian Peninsula and he was voted on the greatest players of the 20th century by World Soccer magazine in December 1999. Not bad for a goalkeepers who played his last competitive match in 1938.

Ricardo Zamora Martinez was, is and probably forever will be one of the biggest names in Spanish football. But his reputation extends beyond the Iberian Peninsula and he was voted on the greatest players of the 20th century by World Soccer magazine in December 1999. Not bad for a goalkeepers who played his last competitive match in 1938.

Born in Barcelona in 1901, El Divino made his name with Español, with whom he won his first Copa del Rey title, before going on to cement his reputation with both Barcelona and Real Madrid. Like most goalkeeping legends, he had his own distinctive style - both in playing terms and appearance - and often entered the field of play wearing a cloth cap and a white polo-neck jumper, which he claimed protected him from the sun and opposition players. He was one the first truly modern keepers and his agility between the sticks was only rivaled by his bravery, playing on in a game against England in 1929 despite breaking his sternum during the match.

In 1920 he was a member for the first ever Spanish international squad and helped his country win silver at the 1920 Olympic games and went on to become Spain's most capped footballer, making 46 appearances in total that including the 1934 World Cup Finals. He kept the record for 38 years and but for the Spanish Civil War, he would have undoubtedly won more.

Having also represented Catalonia, he was an easy target for both Republicans and Nationalists during the War and was exploited by both sides for propaganda purposes. But such was the nature of the conflict that Zamora quickly found himself behind bars - and it was falsely reported that he had been killed during the early stages of the war. However, he remained alive and well, if only because of his willingness to play and talk football with his guards, and was eventually released, spending the next two years with Nice in France.

A colourful, if controversial character, he apparently enjoyed a good a drink and a smoke and first run into trouble with the authorities when he attempted to smuggle Havana cigars into Spain on his return from the Olympics - something that earned him his first stint behind bars. He was later suspended for a year after lying to tax authorities about a signing on fee.

The scandals died down once his playing days were over, but he went on to prove himself as a manager, twice winning La Liga with Atlético Madrid and later managing the Spanish national side. Today, the Ricardo Zamora trophy is awarded to the keeper with the lowest goals-to-games ratio in La Liga - a fitting tribute to a fine player.

Harry Rennie

The chances are that you've probably never heard of Harry Rennie. Yet the former Scotland international was something of a pioneer between the sticks, developing a unique method for keeping goal that was revolutionary at the turn of the 20th Century. Indeed some of the goalkeeping techniques he introduced to the game are still in use today. Quite a remarkable feat when you consider he only became a goalkeeper in 1897 at the relatively late age of 23, after a successful junior career as a half-back.

The chances are that you've probably never heard of Harry Rennie. Yet the former Scotland international was something of a pioneer between the sticks, developing a unique method for keeping goal that was revolutionary at the turn of the 20th Century. Indeed some of the goalkeeping techniques he introduced to the game are still in use today. Quite a remarkable feat when you consider he only became a goalkeeper in 1897 at the relatively late age of 23, after a successful junior career as a half-back.

Rennie made the decision to try his hand in goal when he joined Division Two side Morton. Perhaps it was his inexperience that led to him thinking about his positioning and to help him judge his angles he became the first keeper to mark out his goal area, a practice that is now commonplace. He also introduced a new scientific approach by studying the body language of his opponents as they prepared to shoot, which helped him to anticipate the flight of the ball.

His performances attracted attention from the bigger clubs after a single season he was sold to Hearts for the princely sum of £50, where he won his first international cap the following season, keeping a clean sheet against Ireland in 1900. Less than a year later he was on the move again, joining Hibernian after a proposed move to Celtic fell through due to a contract dispute. As well as being a keen student of geometry, he also had unquestionably faith in his own ability and a stubborn personality is believed to have been the first player to sign for Hibs who negotiated his own terms.

Rennie went on to become an integral part of the team at Easter Road. He won the Scottish Cup in 1902, with contemporary match reports crediting him with a number of important saves, and helped them to their first League title the following year, playing in every game during the campaign and earning rave reviews for his performances.

He collected 13 caps in total and representing the Scottish League a further seven times before moving to Rangers in 1908. Rennie ended his career back at Morton after brief spells with Inverness and Kilmarnock, retiring at the age of 40. He maintained a keen interest in the game and the art of goalkeeping in general, mentoring and developing several talented youngsters, including Jimmy Cowan, who, like Rennie, would go on to represent Morton and Scotland.

Dino Zoff

Despite an inauspicious start to his career, Dino Zoff went on to become one of the best goalkeepers the game as ever known. Such is his standing within football that he was voted the third best keeper of the 20th Century behind Lev Yashin and Gordon Banks in a poll conducted by the IFFHS. Yet just like Peter Shilton before him, his career was almost curtailed at an early age due to his lack of height, a handicap that saw him rejected by both Inter Milan and Juventus.

Despite an inauspicious start to his career, Dino Zoff went on to become one of the best goalkeepers the game as ever known. Such is his standing within football that he was voted the third best keeper of the 20th Century behind Lev Yashin and Gordon Banks in a poll conducted by the IFFHS. Yet just like Peter Shilton before him, his career was almost curtailed at an early age due to his lack of height, a handicap that saw him rejected by both Inter Milan and Juventus.

Legend has it that a diet of eggs recommended by his grandmother Adelaide helped Zoff achieve the necessary height for a goalkeeper and his performances for his local village team attracted the attentions of Udinese. But after conceding five on his professional debut (See Goalkeeping Debuts), Zoff struggled to hold down a first team place. A move to Mantova in 1963 gave the keeper the impetus his career needed and by 1966 the uncapped Zoff was being considered for a place in Italy's World Cup squad by manager Edmondo Fabbri.

In the end, Zoff had to wait another two years before he made his debut for the Azzurri, keeping a clean sheet in a 2-0 victory over Bulgaria in the 1968 European Championships quarter-finals. He would go on to retain his place as Italy beat Yugoslavia in a replay to claim the title. Yet Zoff would play no part in Italy's march to the 1970 World Cup final after a loss of form. Indeed, the World Cup proved to be something of a mixed bag for the Italian goalkeeper.

Omitted from the squad in '66 because the manager did not want to be accused of favouritism, benched four years later, Zoff had to wait until 1974 before he finally made his bow in the competition. But even this proved to be a day of mixed fortunes. After going 1,142 minutes without conceding a goal he was finally beaten by Haiti's Manno Sanon in Italy's opening game in a disappointing tournament for the Azzurri. Ever the perfectionist, Zoff was hugely critical of his own performances in Argentina in 1978 despite Italy's fourth-place finish and it looked like his moment had passed when the unimpressive Italians drew all three of their opening games in 1982 to limp out of their group in the opening round.

However, it would prove to be a happy ending for Zoff, as he led the Azzurri to the title in Spain with a 3-1 win over West Germany in the final, with Golden Boot winner Paolo Rossi singling out his goalkeeper as the most important factor in their unexpected triumph. In the process Zoff became the oldest player ever to win a World Cup medal and only the second goalkeeper to captain his team to victory. It should have been a fitting finale to his international career but having maintained the philosophy that you were only as good as your last game, Zoff remained at the heart of the Italian defence for another year. His swansong proving to be a 2-0 defeat at the hands of Sweden in 1983, the last of his 112 caps.

Renowned for his consistency between the sticks, not to mention his positioning, handling and reaction saves, he collected six Scudetto tiles during his time with Juventus and also won the UEFA Cup and Coppa Italia with the Italian giants. Yet the European Cup was the one trophy that alluded Zoff, missing out twice to Ajax and Hamburg in 1973 and 1983 respectively. However, it wasn't a bad haul for a keeper who had to overcome more than his fair share of disappointments during his career.

Gilmar

Often referred to as "Pele's Goalkeeper", Brazil's Gilmar is often overlooked when fans draw up their list of goalkeeping greats, despite the fact he remains the only custodian to win back-to-back World Cups. Yet in the late 1950s/early 60s, he was mentioned in the same breath as Hungary's Gyula Grosics and the Soviet Union's Lev Yashin and is arguably the best South American goalkeeper of all time.

Often referred to as "Pele's Goalkeeper", Brazil's Gilmar is often overlooked when fans draw up their list of goalkeeping greats, despite the fact he remains the only custodian to win back-to-back World Cups. Yet in the late 1950s/early 60s, he was mentioned in the same breath as Hungary's Gyula Grosics and the Soviet Union's Lev Yashin and is arguably the best South American goalkeeper of all time.

Tall, sleek and clean cut, Gilmer combined agility, quick reflexes and athleticism with an authoritative presence in the box and an unruffled sense of calm. Born Gilmar dos Santos Neves on August 22 1930 in Santos - he was apparently named after his parents, Gilberto and Maria - his talent between the sticks was obvious from an early age with the Jabaquara club in his home city of Santos, where he made his debut at the tender age of 15. He was signed by Corinthians in 1951, going on to win his first piece of silverware the same year when they lifted the state championship. He won the same title three times in his four seasons with the Sao Paulo club and his performances resulted in Gilmar winning his first cap in March, 1953, when he was part of the Brazil side that thrashed Bolivia 8-1 in a Copa America clash.

He quickly cemented his place as first choice for the Selecao, replacing the much-maligned Moacir Barbosa, and came to prominence on the international stage through a string of superb performances during the 1958 World Cup finals. He kept a clean sheet in each of Brazil's first four games of the tournament but is probably best remembered for consoling the emotional 17-year-old Pele after their triumph over Sweden in the final. He conceded just five goals four years later as Brazil successfully defended their title, making a vital save against Spain in a crucial group game to ensure qualification to the quarter-finals, but any hopes of a third success in England in 1966 were short-lived. After keeping goal against Bulgaria and Hungary at Everton's Goodison Park, Gilmar was dropped for the all-important clash against Portugal that saw the holders eliminated after they lost the game.

Having joined his home-city club Santos in 1961, the keeper would continue to enjoy success on the domestic front and played an instrumental part in the team's five successive national championships between 1961 and 1965, plus five Sao Paulo state titles. He also added two Copa Libertadores medals to his collection in 1962 and 1963 and lifted the Intercontinental Cup against Benfica and Milan in the same seasons in a side led up front by Pele, who incidentally scored his first senior goal against Gilmar.

He retired in 1969 at the age of 38, having won his 94th and final cap in a 2-1 friendly win against England at the Maracana in Rio de Janeiro the same year. It was his seventh appearance against the Three Lions, having first showcased his talents to the English public at Wembley back in 1956 in a game where he saved not one but two penalties, the first by Bristol City's John Atyeo, the other by Roger Byrne of Manchester United. Brazil ultimately lost that game but it was just one of 16 defeats experienced by the national side while Gilmar was in goal. No wonder one Brazilian journalist described him as "simply the greatest of all time".

Ronnie Hellström

History has been slightly unkind to Ronnie Hellström. Despite representing Sweden in three consecutive World Cups during the 1970s he is often overlooked when it comes to short-listing the greatest goalkeepers ever to play the game. Yet he enjoyed a distinguished career, if one lacking in silverware, on both the international stage and domestically in his home country and West Germany.

History has been slightly unkind to Ronnie Hellström. Despite representing Sweden in three consecutive World Cups during the 1970s he is often overlooked when it comes to short-listing the greatest goalkeepers ever to play the game. Yet he enjoyed a distinguished career, if one lacking in silverware, on both the international stage and domestically in his home country and West Germany.

His standing within the game is more remarkable when you consider that he played part-time for the first eight years of his career with Swedish side Hammarby. Something of a precocious talent, he made his debut at the tender age of 17 before winning the first of 77 caps two years later in a friendly against the Soviet Union. By the time the 1970 World Cup came around, he was Sweden's first choice keeper but an uncertain game against Italy in their first match of the tournament saw him dropped in favour of Sven-Gunnar Larsson.

Hellström bounced back the following season, however, and was voted Footballer of the Year (Golden Ball) in his home country in 1971. He would continue to play for Hammarby for another three years before finally turning professional when he joined Kaiserslautern, prior to the 1974 World Cup. Having begun to carve out a reputation as an instinctive shot stopper and something of reflex save specialist, Hellström, with his blond locks and moustache, enjoyed an excellent tournament in West Germany and helped Sweden to an unexpected fifth place in the competition. Had he not been so eager to sign professional forms, he could arguably have had his pick of the big European clubs such was the level of his performances.

However he had no regrets about joining the Red Devils and spent the remaining ten years of his career with the club. He won his second Footballer of the Year in Sweden in 1978 and enjoyed further positive reviews in the World Cup in Argentina in the same year, where the Swedes were eliminated in the first round after being drawn in the same group as Austria, Brazil and Spain. Despite the early exit, Hellström was at the peak of his game and conceded just three goals - one in each game.

Yet club honours continued to elude him. He picked up two German cup runners-up medals in 1976 and 1981 and narrowly missed out on a UEFA Cup medal when Kaiserslautern were knocked out of the semi-finals, ironically by Gothenburg, in extra time. But throughout his time with the German club he remained a popular figure with the fans. The love affair was mutual and when the New York Cosmos came calling, Hellström decided to stay. When he retired in 1984, he was rewarded with a farewell game, the first non-German to receive the honour. Broadcast live on television in both Germany and Sweden, the match drew a gate of 35,000 and saw the goalkeeper carried off the shoulders of his adoring fans.

He would make on further appearance, turning out at the ripe old age of 39 for GIF Sundsvall after an injury crisis robbed them of both of their regular keepers. Typically, and somewhat appropriately, Hellström kept a clean sheet.

Alan Hodgkinson

Alan Hodgkinson was a one club man, spending his entire professional career at Bramall Lane with Sheffield United. He won five England caps and was back-up to Ron Springett during the 1962 World Cup in Chile but never enjoyed the kind of domestic success experienced by his contemporaries. No FA Cup final appearance, no European jaunts, no League titles. Yet his place in history is assured by his contribution to the art of goalkeeping after his playing career came to an end, having effectively invented and introduced the role of professional goalkeeping coach to the British game in the 1980s.

Alan Hodgkinson was a one club man, spending his entire professional career at Bramall Lane with Sheffield United. He won five England caps and was back-up to Ron Springett during the 1962 World Cup in Chile but never enjoyed the kind of domestic success experienced by his contemporaries. No FA Cup final appearance, no European jaunts, no League titles. Yet his place in history is assured by his contribution to the art of goalkeeping after his playing career came to an end, having effectively invented and introduced the role of professional goalkeeping coach to the British game in the 1980s.